Brief Note:

We are delighted to welcome several new subscribers to our ranks! Thank you for being a part of our learning, thinking, reading community here at Think On These Things—we hope you will consider sharing our content with others who might appreciate it. For those getting to know us for the first time, we invite you to revisit this inaugural edition, as well as our earlier series on Truth, Beauty, and Excellence as our founding values.

Greetings, Readers!

Have you ever experienced a work of art that stays with you? I don’t mean the silly ones that make your head spin. I’ll never forget one of the “modern art” exhibits that I saw in Chicago where there were stations posited as art—a stack of plain computer paper or a bowl of candy, both of which were intended to show interactive art because they could be diminished and then replenished. That is something entirely different.

I mean works of art that stick with you because of a captivating image or wondrous scene that beckons beyond its canvas. In contrast to the imposter example above, I will also never forget the first installation art exhibit that I experienced. A classmate was premiering her collegiate work. The gallery was displayed in a way that took the guest through several pathways—the most intriguing, an arched trellis walkway, inside which a series of works were displayed. It depicted the journey of a young lady who was wrestling with pain, identity, and brokenness as she upheld the masked façade of her life—displayed by darkness, broken mirrors (which we crunched underfoot as though it had fallen out of the display), a stage, and painted faces evoking emptiness and despair. And then, as the journey continued, she found her way to hope; instead of pieces of broken mirror on the painting and ground, there was her broken mask as she cast it off and became free. It was a moving experience.

One of the other paintings was touching in a different way. The artist had beautifully painted a pianist seated at the instrument; reflected in the shiny, black piano were features of the musician—his hands on the keys and his heart. This piece was incredibly intimate as the artist knew this particular pianist, her dear friend who was an accomplished pianist but had lifelong, repeated open heart surgeries. This piece had layers of meaning, beauty, and depth.

The personal nature of any artist makes its way into the work. Like any fine piece of music, literature, or architecture, fine art allows us to delve into the world of its artist to uncover the layers beneath the surface of what we see. Throughout history, art has been a representation of its culture, people, and time—and it is our job to not only enjoy the beauty of what has been created, but also to understand its context and purpose. After all, how are we to sufficiently grasp the meaning of Picasso’s work without understanding the nuance of his style, beliefs, historical context, or motivation? Why did Degas painted so many dancers? What was churning beneath the surface when Van Gogh produced his most famous work while in a mental institution? Suffice it to say, art blends the style, technique, format, and talent of its artist’s own story, purpose, life experience, demons, joys, hopes…and on and on.

The result is an infinite amount of creativity, beauty, meaning, richness, wonder, and exploration into the complexity of our world and ourselves. Good art has a unique and profound way of speaking into our lives. This edition, we will explore the story of one scholar’s life-changing encounter with Rembrandt.

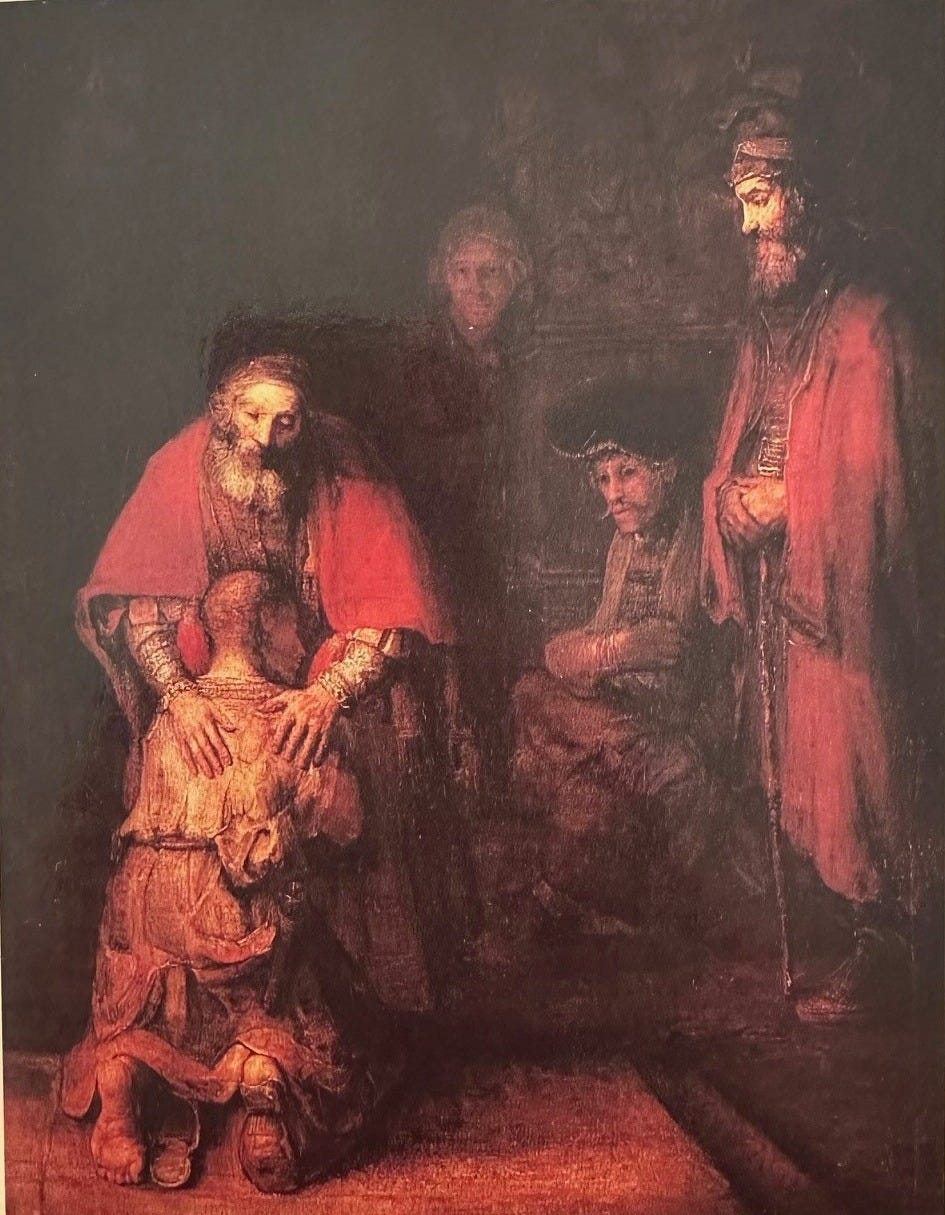

It all started with a glimpse of this work: The Return of the Prodigal Son.*

The Return of the Prodigal Son is one of the most famous works of Rembrandt (1606 – 1669), the Dutch painter who has been etched into the canon of western art and history. He became known for his deep works depicting biblical and mythical scenes, as well as his prolific output of portraits that served as an important source of income during his life. During the Baroque era, art and music had started to emerge out of more exclusively religious contexts, and most of the artistic expertise of musicians and painters would have been commissioned for the church. By the early 1600s, the arts broadened beyond religious uses and began expanding into other forms depicting myth, nature, portraits, and realistic depictions of people in various activities.

This is evident across the scope of Rembrandt’s work, which we encourage readers to explore and study further. He masterfully experimented and executed elements of light that bring depth to his works—and his depiction of people, faces, and eyes are quite powerful. Many of these elements are on full display in this Prodigal Son masterpiece, which came to life near the end of his own. Perhaps that is what gives its characters so much complexity. A life that had already encountered the follies of youth, the highs of success, the lows of death and sorrow, the reality of its own selfish gain, and finally the settling into older age and a sense of peace.

However, there is a story that has emerged alongside this painting from a current contemplative soul that is worth exploring. Our primary source text here is Henri J.M. Nouwen’s book The Return of the Prodigal Son: A Story of Homecoming, where we get a glimpse into both Nouwen’s and Rembrandt’s stories—and perhaps some of our own, as well.**

Nouwen’s personal account of his encounter with Rembrandt’s culminating work is one of the most moving examples that I’ve seen of what can happen “when art speaks”. He describes the moment he first saw a reproduction print of The Return of the Prodigal Son and how it would not let go of him. What followed was a journey to visit the original at the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, research the artist’s life and work, and embody the layers of meaning from both the painting and the original parable in his role as pastor of a community of people with disabilities. For Nouwen, who left prestigious roles in Ivy League institutions (including Yale and Harvard Divinity Schools), you might say that his encounter with this painting allowed him to grasp hold of something far more real, raw, and rich that he had previously known.

I suspect most of us can relate to Nouwen’s words:

“I felt that, if I could meet Rembrandt right where he had painted father and son, God and humanity, compassion and misery, in one circle of love, I would come to know as much as I ever would about death and life. I also sensed the hope that through Rembrandt’s masterpiece I would one day be able to express what I most wanted to say about love…

Moving from teaching university students to living with mentally handicapped people was, for me at least, a step toward the platform where the father embraces his kneeling son. It is the place of light, the place of truth, the place of love. It is the place where I so much want to be, but am so fearful of being. It is the place where I will receive all I desire, all that I ever hoped for, all that I will ever need, but it is also the place where I have to let go of all I most want to hold on to. It is the place that confronts me with the fact that truly accepting love, forgiveness, and healing is often much harder than giving it. It is the place beyond earning, deserving, and rewarding. It is the place of surrender and complete trust.”

His account in the book provides remarkable parallels of Rembrandt’s stages of life to that of the three main characters in the painting—the son, the older brother, and the father. Again I suspect that most of us will find some relatable elements of our own lives and complexities hidden within the full range of these characters. This is precisely what spoke to Nouwen and secured his own journey to follow his unique calling, or as he describes it, his “homecoming”.

Having studied Rembrandt’s final two works in tandem, he notes the role of light and the role of seeing:

“The more I read about it and look at it, the more I see it as a final statement of a tumultuous and tormented life. Together with his unfinished painting Simeon and the Child Jesus, the Prodigal Son shows the painter’s perception of his aged self—a perception in which physical blindness and a deep inner seeing are intimately connected…Both Simeon and the father of the returning son carry within themselves that mysterious light by which they see. It is an inner light, deeply hidden, but radiating an all-pervasive tender beauty. This inner light, however, had remained hidden for a long time. For many years it remained unreachable for Rembrandt. Only gradually and through much anguish did he come to know that light within himself and, through himself, in those he painted. Before being like the father, Rembrandt was for a long time like the proud young man who ‘got together everything he had and left for a distant country where he squandered his money.’”

So, let’s dig into these three characters.

Finding Rembrandt in the Character of the Prodigal Son:

The younger brother/prodigal son is a classic character. He is the age-old tale of someone being on the wrong path for life and then turning to the right path—in present day, we might think of the addict, the drop-out, or the partier finally getting his/her act together and growing up, shaping up, and straightening things out for a successful life. But what Nouwen helps us dig into is a much more tender side of this character and artist, a side that we only see when he encounters the father. From Nouwen’s perspective:

“As I look at the prodigal son kneeling before his father and pressing his face against his chest, I cannot but see there the once so self-confident and venerated artist who has come to the painful realization that all the glory he had gathered for himself proved to be vain glory. Instead of the rich garments with which the youthful Rembrandt painted himself in the brothel, he now wears only a torn undertunic covering his emaciated body, and the sandals, in which he had walked so far, have become worn out and useless.”

To adequately understand his homecoming, we must first understand his vain glory days.

“…all the Rembrandt biographers describe him as a proud young man, strongly convinced of his own genius and eager to explore everything the world has to offer; an extrovert who loves luxury and is quite insensitive toward those about him. There is no doubt that one of Rembrandt’s main concerns was money. He made a lot, he spent a lot, and he lost a lot.

However, this short period of success, popularity, and wealth is followed by much grief, misfortune, and disaster. Trying to summarize the many misfortunes of Rembrandt’s life can be overwhelming. They are not unlike those of the prodigal son.”

Rembrandt encountered the loss of many children, his beloved wife, a tumultuous affair with his surviving son’s nurse—whom he later forced into an asylum—and a downward spiral in his career and eventual financial devastation.

His life certainly saw the full scope of highs and lows. But, the harsh sanding of life’s realities—much of which was brought on of his own decisions and doing—eventually brought him to a place of more human understanding. Nouwen proposes that this complexity of Rembrandt’s own character is what allows him to paint such depth into each of the very different characters in this painting.

“Although Rembrandt would never become completely free of debt and debtors, in his early fifties he is able to find a modicum of peace. The increasing warmth and interiority of his paintings during this period show that the many disillusionments did not embitter him. On the contrary, they had a purifying effect on his way of seeing. Jakob Rosenberg writes: ‘He began to regard man and nature with an even more penetrating eye, no longer distracted by outward splendor or theatrical display.’”

Finding Rembrandt in the Character of the Older Brother:

The older brother is often the more difficult character to grasp. In the original parable, it’s not hard to understand the younger brother/son, who has squandered his life and made a mess of things. It’s much more obscure to sift through the smoldering, proud resentment of the older brother who has yet to come to a place of humility and receive the love, extravagance, and inheritance of his father.

Here, too, we see a more sinister side of Rembrandt, which is equally difficult to grasp. Nouwen explores the pull of “the inner drama of the soul” that is displayed in the older brother. There is evidence that Rembrandt knew this all too well.

“Many biographers are, in fact, critical of the romantic vision of his life. They stress that Rembrandt was much more subject to the demands of his sponsors and his need for money than is generally believed, that his subjects are often more the result of the prevailing fashions of his time than of his spiritual vision, and that his failures have as much to do with his self-righteous and obnoxious character as with the lack of appreciation on the part of his milieu.

In particular, the biography by Gary Schwartz—which leaves little room for romanticizing Rembrandt—made me wonder if anything like a ‘conversion’ had ever taken place. Schwartz describes him as a ‘bitter, revengeful person who used all permissible and impermissible weapons to attack those who came in his way.’

This is most vividly shown in the way he treated Geertje Dircx, with whom he had been living for six years. He used Geertje’s brother, who had been given the power of attorney by Geertje herself, to ‘collect testimony from neighbors against her, so that she could be sent away to an insane asylum.’ The outcome was [her] confinement in a mental institution. When the possibility later arose that she could be released, ‘Rembrandt hired an agent to collect evidence against her, to make certain that she stay locked up.’”

This disturbing scene reveals a hardened Rembrandt, during a period when his popularity as an artist was waning, financial hardship was growing, and his work output was nonexistent. What a convergence of his own pride, desperation, and cruelty.

This character is harder to love, and as Nouwen describes, more reluctant to change. He suggests: “Both needed healing and forgiveness. Both needed to come home. Both needed the embrace of a forgiving father. But from the story itself, as well as from Rembrandt’s painting, it is clear that the hardest conversion to go through is the conversion of the one who stayed home.”

Finding Rembrandt in the Character of the Father:

Thank goodness for the character of the father! If the story ended there, it would be bleak indeed. Not surprisingly, the father is the culminating figure of both the parable and the painting, and the source of goodness in the story. As Nouwen sees it, he is also the culminating character of Rembrandt’s life. While the original parable stands on its own and carries the primary message, this painting is a powerful interpretation of it due in large part to Rembrandt’s own journey in life.

Here we come full circle to Nouwen’s observation about the physicality that Rembrandt displayed in his later works—surely a skill that he refined over decades of portraits and depictions of everyday human activity—and see that every stroke of the brush creates an intentional portrayal of deeper meaning.

“Every detail of the father’s figure—his facial expression, his posture, the colors of his dress, and, most of all, the still gesture of his hands—speaks of the divine love for humanity…Here, both the human and the divine, the fragile and the powerful, the old and the eternally young are fully expressed. This is Rembrandt’s genius. The spiritual truth is completely enfleshed. As Paul Baudiquet writes: ‘The spiritual in Rembrandt…pulls its strongest and most splendid accents from the flesh.’”

We will leave it to you to explore how and where the depth of Rembrandt’s work speaks to you! Your story may be quite different from those of today’s featured artist and scholar, but great art inevitably speaks to each of us in a unique way. In this work, there are any number of elements that may take hold and not let you go—perhaps the use of light or sight, or the shadowy figures of the onlookers, the intimacy between the father and son, or the story itself?

Whatever catches your eye or your soul, we encourage you to dig deeper into the many facets of this painting—its artist, time period, origin story, and techniques. Perhaps you, too, will encounter the wonder that Henri Nouwen so authentically shares in his personal account. And, be sure to pick up his short book and experience his full journey of encountering this masterpiece. Perhaps you will even travel afar to see the original one day!

*If you have not ever read the original parable of the prodigal son, you can find that original source text in the biblical account of Luke, chapter 15. (to read it, click here)

**To learn more about Henri Nouwen or purchase his book, you can visit: https://henrinouwen.org/read/the-return-of-the-prodigal-son/.

Think on These Things publishes new content every other Friday. Be sure to subscribe and share with a friend!

For more content, be sure to follow us on Instagram, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

Thanks, CS! Having never taken art appreciation courses or in depth exhibit tours, I will never look at art the same again. Reading this interpretation has made me excited to explore all forms more deeply for meaning and context!