Greetings, Readers!

Welcome to our newest subscribers. We are delighted that you’ve joined this community of learners and thinkers. If this is your first edition of Think On These Things, be sure to take a look at our inaugural series where we share the framework by which we explore content. You can see earlier editions here.

Last edition we landed in the heart of the 19th Century, exploring the poetry and life of a woman who brought us the triumphant Battle Hymn during the American Civil War. This week, we remain in the same era and travel to Italy to enjoy an extraordinary masterwork that continues to stand the test of time—Giuseppe Verdi’s Requiem. We will, without a doubt, merely scratch the surface of a life, musical era, and composition that could justify pages and pages; however, today’s purpose is to introduce those elements and send you on your own learning and listening journey. We hope this inspires you to delve deeper into the magnificent realm of Western Classical music.

The Composer

Composed in 1873 and premiered in Milan in 1874, this work features the intensity, beauty, and drama that have become hallmarks of Verdi’s beloved style and the Romantic era. By this late period of his career, Verdi (1813 – 1901) had mastered musical lines that played out in service of dramatic text. This, in contrast to the immediately preceding bel canto era, where operatic storylines would routinely pause in order for a singer to “wax eloquently” during arias that featured repeats to allow for virtuosic ornamentation. While Verdi’s early works were on the heels of this style, and certainly influenced by it, he conjured musical drama early in his career with works like Nabucco (1841), which continued through his career with his most famous trio of Rigoletto, Il Trovatore, and La Traviata and later with works like Aida, Don Carlo, and others. The constants over time included his love of the operatic genre and his commitment to choosing storylines and librettos/texts that were sufficiently suited to his flare for the dramatic.* His music encompasses the full scope of virtuosic vocal lines (enhanced by the scena ed aria form – a more integrated and seamless flow between recitative and aria), rich beauty, robust orchestral instrumentation, lush choruses, and music that fits like a glove to its complex characters. As the musical progression into the Romantic era continued, the music also developed in its size and scope, thus requiring larger voices to carry over the heavy instrumentation. Yet, with Verdi, the beauty of vocal lines and melodies is maintained. Chances are, you might recognize some of his most famous areas, akin to modern day showstoppers (such as “Caro Nome” from Rigoletto, “Sempre Libera” from La Traviata or or “Ritorna Vincitor” from Aida…there are many more!).

The Work

Our main course for this edition, his Requiem, falls near the point of his retirement. Having started a collaborative requiem mass with several other composers in 1868 after the death of beloved bel canto composer Gioachino Rossini (which did not come to fruition), he set out once again in 1873 to memorialize Italian poet Alessandro Manzoni—this time finishing the work. After its premiere at San Marco, it was performed several times at La Scala. Here is an account of the work’s inception from German musicologist Wolfgang Stähr:

The Italian poet Alessandro Manzoni died in his home town, Milan, on 22 May 1873 at the great age of 88, revered throughout Italy and beyond. Verdi was so upset by the news that he could not bring himself to attend the funeral. “It’s the end of everything! And with him our purest, most sacred, greatest glory comes to an end.” There was something almost religious about Verdi’s enthusiasm for Manzoni, infused the spirit of the Risorgimento and a climate of national fervour: he regarded him as a “model of virtue and patriotism”. For him, composing a requiem for performance in Milan on the first anniversary of Manzoni’s death was an obvious thing to do: a monumental setting of the Latin Mass for the Dead for four soloists, chorus and orchestra, conjuring all the terrors of the Last Judgement, the fear of death, bereavement and the promise of salvation, right up to the fearful, unresolved end of the “Libera me”. For the first performance on 22 May 1874, which he conducted himself, Verdi chose neither a concert hall nor a theatre but Milan’s San Marco church, which he considered better acoustically than either the cathedral or the church Manzoni himself attended, San Fedele. Only a church was appropriate for the commemoration of a sincere Catholic like Manzoni, who had foreseen national renewal in faith. Goethe, who admired Manzoni’s sacred poetry as much as he did the historical novel I promessi sposi (The Betrothed), characterized Manzoni as a “Christian without raptures, Roman Catholic without bigotry, a zealot without rigor.”

The Performance

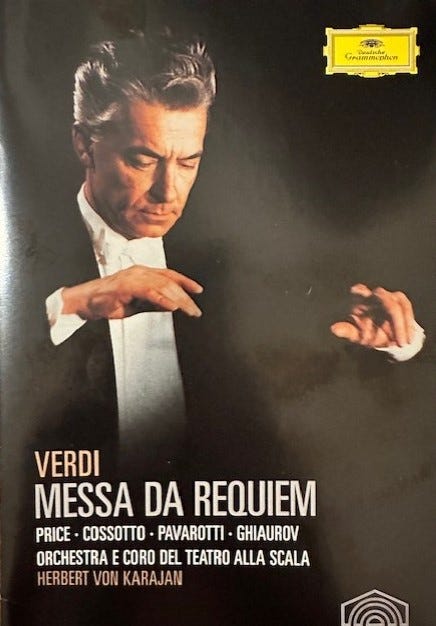

The live recording shared with you here is truly extraordinary! Similarly to the Requiem’s origin story, the 1967 performance took place for the ten year anniversary of Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini’s death. Fittingly, it took place at La Scala where Toscanini spent many years at the helm.

Austrian conductor Herbert von Karajan, beloved by many singers, assembled arguably the finest cast of singers to ever join forces to perform this masterpiece. Alongside an orchestra and chorus that superbly displays the full range of musical emotion and intensity called forth by the score (and Karajan’s conducting - from memory, by the way), the backdrop is set for four truly remarkable soloists to soar.

The Soprano

The great American soprano, Leontyne Price delivers a flawless and commanding performance. Karajan held a special place in her career story and became one of her greatest champions. Schuyler Chapin, general manager of The Metropolitan Opera from 1972 – 1975 describes their introduction this way in his book, Sopranos, Mezzos, Tenors, Bassos, and Other Friends: “My professional association with Leontyne Price began with her now-famous 1954 audition for Herbert von Karajan, which took place late one fall afternoon at Carnegie Hall. At the urging of impresario Walter Legge and concert manager Andre Mertens, Karajan agreed to hear her, and became so enthused that he bounded out of his seat and onto the stage where, after a few admonitions, he eased her accompanist aside and began to play for her. Later that same afternoon…Karajan made it clear he would make her a world star if, from here on in, he had first call on her European activities.”

The Mezzo

Fiorenza Cossotto, the Italian mezzo soprano, displays her rich, lush tone. Having spent the bulk of her career performing at La Scala and The Metropolitan Opera, she was well versed in maintaining both dramatic and delicate vocal mastery. Amidst her peer soloists, her sizable mezzo carries beautifully even when all voices are in full force.

The Tenor

No doubt a familiar name to most, Italian tenor Luciano Pavarotti stands tall as a young star in this recording. This recording was at the beginning of Pavarotti and Karajan’s tenure working together and they would go on to record several other projects, building a lifelong rapport as they became two of operas most notable figures of the 20th Century. Karajan described Pavarotti as “a voice that only appears once in a hundred years.” Notably, he is the only singer using a score—he ended up standing in for famed tenor Carlo Bergonzi, who was not available to sing the performance, so perhaps he had little time to prepare.

The Bass

Nicolai Ghiaurov was a Bulgarian bass who also graced opera stages. His path to La Scala was a longer one, as he spent his early career in Sofia and Moscow, eventually landing a role at the storied Italian opera house. He also worked with Karajan at the Salzburg Festival in 1965.

As you can see, all roads lead (not to Rome as the saying goes) to La Scala in this case…and to Karajan. It’s not difficult to see the importance of this conductor’s work woven throughout the lives and careers of such an extraordinary cast of singers. They do beautiful justice to Verdi’s musical masterpiece. We commend this recording to you and hope you will carve out some time to listen to the full work in its entirety.

Happy listening!

*Verdi’s own life had plenty of drama in its own right! His first wife died at a young age, following the death of his two children; he sank into a deep depression and grief; he later married again to the star of his first operatic work; and eventually had an affair with another soprano.

Think on These Things publishes new content every other Friday. Be sure to subscribe and share with a friend!

For more content, be sure to follow us on Instagram, Facebook, and LinkedIn.