Greetings, Readers!

Before there was talk of GOATs, there was talk of greats. Whether in the realm of sports, music, literature, or art, these elite best-of-the-best are simply unmistakable. As a classically trained singer, this has me dusting off memories of countless college evenings when peers would gather for opera listening “parties” where we would hone our skills and try to earn our stripes by naming the correct singer after hearing an unknown recording. In a single performance, there were all sorts of clues to help us discern a guess—the timbre of the voice, type of repertoire, stylistic choices, instrumentation, other singers/cast, quality of recording, vocal technique, ebbs and flows of vocal registers and how they were navigated. (You could, perhaps, liken it to a blind taste test between wine connoisseurs.) Over and over again, it was proven true that the greats were unmistakable.

Have you ever wondered why?

Certainly, in any genre or discipline there are the actual metrics that quantify rankings, but that’s not what we are talking about here. We are talking about the phenomenon that captivates us when we witness someone performing at the height of calling and capability. Earlier editions where we discussed beauty and excellence touched on these moments pointing to something bigger than simply what we see or hear—the sense of the eternal that calls to our souls.

I’d like to suggest that it is this deeper sense of something eternal that resonates with us each time we experience one of the greats in action. It’s why we watch the Olympics. It’s why we love to hear the most complex and beautiful music flawlessly performed, or why we want to see the singer hit the high note! It’s why we want to see world records broken by our athlete of choice, and why halls of fame are hallowed. It’s why great works of art like paintings or cathedrals stop us in our tracks until we cast eyes on their beauty and try to discern the meaning behind them. Our souls crave the supernatural—and this tells us something about ourselves and something about the world in which we live.

There is a concept from early Christian writings and theologians that speaks to this (whether or not you are a person of faith, I trust you will glean and/or relate to its meaning). Fundamental to the concept is the biblical principle that people are created in the image of God, and thereby reflect that image most poignantly when living into one’s truest form of purpose. Irenaeus of Lyons’ monumental treatise Against Heretics (roughly 180 A.D. – you can read the original here) notes “For the glory of God is a living man; and the life of man consists in beholding God.” While immediate context is referencing Christ and His purpose on earth as the incarnate God, the broader concept is often used to encourage followers of Christ toward their unique purpose—essentially the notion that being “fully alive” and thriving into one’s purpose is the best way to bring glory to the One who created them for that purpose. The concept has been commonly extrapolated across other theological works and essays.

We see elements of this in the Westminster and Heidelberg Catechisms when answering the question, “What is the Chief End of Man?”, and its corresponding response that it is “To Glorify God and Enjoy Him Forever”.

Father Jacques Philippe discussed this within the framework of peace in his delightful work Searching for and Maintaining Peace: A Small Treatise on Peace of Heart when he said:

To permit the grace of God to act in us and to produce in us all those good works for which God prepared us beforehand, so that we might lead our lives in the performance of good works it is of the greatest importance that we strive to acquire and maintain an interior peace, the peace of our hearts…Consider the surface of a lake, above which the sun is shining. If the surface of the lake is peaceful and tranquil, the sun will be reflected in this lake; and the more peaceful the lake, the more perfectly will it be reflected. If, on the contrary, the surface of the lake is agitated, undulating, then the image of the sun can not be reflected in it. It is a little bit like this with regard to our soul in relationship to God. The more our soul is peaceful and tranquil, the more God is reflected in it, the more His image expresses itself in us, the more His grace acts through us.

C.S. Lewis discussed this concept in his essay titled Membership in which he explores the nature of purpose. He says it this way:

It will not be attained by development from within outwards. It will come to us when we occupy those places in the structure of the eternal cosmos for which we were designed or invented. As a colour first reveals its true quality when placed by an excellent artist in its pre-elected spot between certain others, as a spice reveals its true flavour when inserted just where and when a good cook wishes among the other ingredients, as the dog becomes really doggy only when he has taken his place in the household of man, so we shall then first be true persons when we have suffered ourselves to be fitted into our places. We are marble waiting to be shaped, metal waiting to be run into a mould.

And so, as we bask in the beauty—and even glory—of one of the greats performing at the height of her unique purpose, I encourage you to Think On These Things.

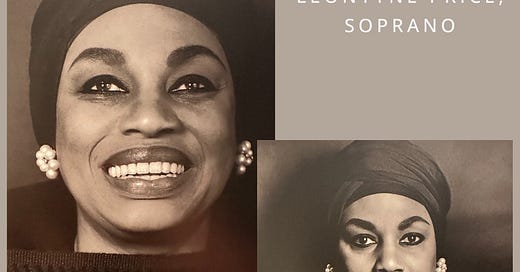

Let’s meet our inspiration, the legendary operatic soprano Leontyne Price.

Leontyne’s Moment of Inspiration

The story of Leontyne Price is remarkable in its own right. Born in 1927 during the Jim Crow era south in Laurel, Mississippi, there were plenty of reasons for her unique purpose as an African American woman to have never graced our stages in such a public and revered way. But there were also plenty of reasons that she did. The most important is that of her family—her parents were hard working and dedicated to their family, and by all accounts set an incredible example for how to live a life of meaning, diligence, excellence, dignity, and faith (both of Leontyne’s grandfathers were Methodist ministers). In addition, they were attentive to Leontyne’s early musical giftings and committed to fostering her growth. Having started piano lessons at a young age and graduating to a real upright piano at the age of 8, Leontyne quickly expanded into musical roles at both church and school to help with the choir. Her parents sacrificed to make her musical training—and later college for her and her brother—possible. In an account of his close working relationship with Leontyne, Schuyler Chapin, former General Manager of The Metropolitan Opera, writes:

There were five people in the story of Leontyne’s life who were crucial to her development, and they all lived in the little Mississippi town of Laurel, where she was born and named Mary Leontyne Violet Price. Her mother, Katherine Price, was a strong, proud woman who taught her daughter the art of getting along in a white-dominated world and, in later life, became a midwife and pillar of Laurel’s black community; her father, James Anthony Price, was a quiet, reflective man who earned a living as a carpenter; and third was a favorite aunt, known to the family as “Big Auntie,” who followed Leontyne’s development with avid interest and worked as a maid in the home of a white couple named Chisholm.

But I’d like to highlight Leontyne’s moment of inspiration, which seems to have drawn on the very greatness that we’re discussing. She had the opportunity to hear Marian Anderson in recital—the first African American opera singer to perform at The Met, though very late in her career, and someone who was known for her poise and dignity as a professional, which became an important marker of Leontyne’s demeanor. This is the moment that she describes as igniting her inspiration for running towards her own purpose as an opera singer. Here is Chapin’s account of her own words:

“I was nine and a half,” Leontyne recalls, “when I first heard Marian Anderson. It was just a vision of elegance and nobility. It was one of the most enthralling, marvelous experiences I’ve ever had. I can’t tell you how inspired I was to do something even similar to what she was doing. That was what you might call the original kickoff.”

I suspect many of us have experienced moments like this in our own lives, when we get a glimpse of clarity and vision around our unique calling in this world. Happily for us, Leontyne stepped with her own elegance and nobility into hers.

Leontyne’s Moment of Invitation

It would be several years later when Leontyne was at Central State College that she would take an important step toward her future greatness. In another impactful moment, she was invited up on stage. Again in Chapin’s words:

Paul Robeson, the great black baritone, visited Antioch to do some lecturing and singing, and at his recital there he invited Leontyne to sing part of the program with him, giving her a portion of the receipts. She saved this money, augmenting it by working at the college cafeteria. On graduation, she made straight for New York, where she got a scholarship at the Juilliard School.

Leontyne’s Rise to Greatness

The rest, as they say, is history. From Juilliard onward, where she met her longtime and beloved voice teacher Florence Page Kimball, Leontyne began taking the operatic world by storm. She credits Kimball as the one who taught her to sing—and famously “taught her to sing on the interest and not the capital” of her voice. To quote Leontyne herself, “Every gift given by the Man upstairs, it has certain qualities that are you as a person and you should merge those as soon as possible and nourish them each and every time you are out on stage…and with it comes, what is I think imperative…which is the thrill of singing, your own self, the thrill that you have sending your talent out to the public.”

She landed a life-changing audition with conductor Herbert von Karajan in 1954 that would launch her European circuit. Her American debut was with the San Francisco Opera in 1957, but it is another debut that we wish to highlight here. (For the sake of space, we will point you to some resources that discuss her career—we have covered it briefly in a previous edition and then this account from The Metropolitan Opera.)

There is a truly remarkable moment in her life and career—and in the lives of audience members present on January 27, 1961—when Leontyne Price made her Metropolitan Opera debut alongside another great, Italian tenor Franco Corelli, in Verdi’s Il Trovatore. As the story goes, the audience was so awestruck that they gave a 42-minute standing ovation at the finale. If you can imagine a day and age when audiences did not jump to their feet as easily as they do today, you can begin to understand the weight of this visceral response (in fact, if you go even further back in history, you may recall that audiences regularly booed bad performers off the stage, or worse, threw things at them - one of Verdi’s early operas was “hissed off the stage”!).

Could it be that witnessing two of the greats stirred something of the eternal amongst the souls in this audience?

Not surprisingly, Leontyne would go on to many more performances at The Met—including the opening night debut of Samuel Barber’s Antony and Cleopatra, which was commissioned to commemorate the opening of the new opera house when it moved from its original location at Broadway and 39th Street to its new location at Lincoln Center in 1966.

But the glory of her “fully alive” calling is hard to deny when exposed to the recordings of her voice that we enjoy, as well as the accounts of all who got to hear her in a live performance. She is, indeed, unmistakable.

Leontyne’s Moment of Reflection

It is, perhaps, fitting to close our ponderings with something personal from her dear friend who has guided much of our understanding of her story. Here are Chapin’s tender words:

Simply put, she is one of the glories of America, as a woman, an artist, and a human being…She is, in the parlance of the day, ‘some piece of work!’ or, to put it in slightly more dignified terms, she is, alongside William Faulkner and Eudora Welty, Mississippi’s greatest cultural gift to world civilization.

I think Leontyne would value his generous words; but I think she also had a deep understanding of her purpose in this world. Here is her own remembrance of the monumental moment when she was called upon to open The Met’s new opera house. What was universally conveyed in her singing is spoken here as she reflects on the honor of being selected to represent both the opera house and her country. Her words, “Now Laurel really set in…Mama and Daddy really set in. Everything, all my teachers really set in and I thought, ‘okay!’, because the whole point was for it to be an all-American occasion. That whole year…I did nothing that would possibly interfere with my being at my total, complete best. I was just so determined that I was going to do my country proud.”

She did, indeed, do her country proud and—in her own words—”the Man upstairs”, too.

This interview with her at the age of 81 is delightful - and she shares some phenomenal wisdom that can apply to many disciplines and careers in life:

For your listening pleasure:

Here is the infamous 1961 Met debut with Franco Corelli that garnered a 42 minute standing ovation. While this isn’t the finale, it’s not hard to hear the explosive applause and cheering at the end of each of her arias - the audience simply cannot contain itself!

And a glimpse of her shining co-stars, American baritone Robert Merrill as the Count and Italian tenor Franco Corelli in the role of Manrico:

Leontyne was also beloved for her spirituals:

Lee Hoiby’s Winter Song:

And, of course, her final legacy role, Verdi’s Aida:

Think on These Things publishes new content every other Friday. Be sure to subscribe and share with a friend!

For more content, be sure to follow us on Instagram, Facebook, and LinkedIn.